|

| Grotesques from Reims, France, photographed by Joseph Trompette (ca. 1870-90) (via Cornell University Library) |

The Squonk

This sad, mythical creature hails from the legends of northern Pennsylvania. The Squonk was said to be a hideous forest animal with grotesquely loose, scaly skin entirely covered in warts and blemishes.

|

| The Teary Squonk - Indrachapa J - Medium |

|

| The squonk as illustrated by Coert Du Bois from Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods. photo: wikipedia |

The animal was so miserable over its own gruesome appearance and lack of companionship that it almost constantly wept. Local legend had it that the Squonk was quite easy to track; you could pretty much just follow the sound of the animal’s sobs and salty, tear-strewn trail through the woods. Capturing one proved much harder: when greatly distressed the Squonk was said to literally dissolve into a puddle of its own tears.

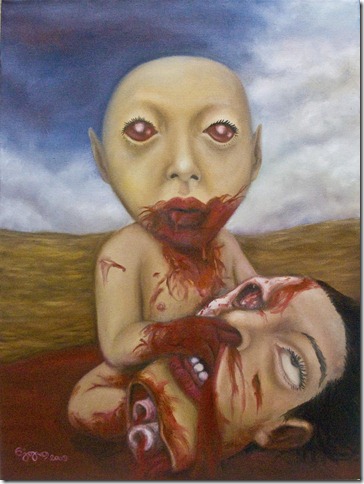

The Tiyanak

The Tiyanak takes various forms in Philippine mythology. In one version it is an evil dwarf-like creature posing as a human baby, in another it is an actual demon child.

|

| The Demon Child Vampire Tiyanak photo: bookroar |

|

| T is for Tiyanak - Supposedly the "true" form of the tiyanak |

The Tiyanak also enjoys confusing travelers into losing their way, leading them deeper and deeper into the Philippine jungle with its cries. If you ever find yourself being lured astray by this monster baby, the traditional trick for escape is to turn your clothes inside out. According to Philippine lore, this amuses the Tiyanak to no end, and he may just think that you’re funny enough to let you live.

The Cat Sìth or Cat Sidhe

The Cat Sìth is a fairy creature from Celtic mythology, said to resemble a large black cat with a white spot on its chest. Legend has it that the spectral cat haunts the Scottish Highlands. The legends surrounding this creature are more common in Scottish folklore, but a few occur in Irish. Some common folklore suggested that the Cat Sìth was not a fairy, but a witch that could transform into a cat nine times

|

| An Illustration from More English Fairy Tales from the story The King of the Cats photo: wikipedia |

|

| Fairy Myths: The Cat Sidhe The Paranormal |

A large, dog-sized breed of black and white cat said to roam the Scottish Highlands, the Cat Sìth was believed to steal the souls from newly deceased bodies awaiting burial. In a wake called the Feill Fadalach (aka the “Lake Wake”), unburied bodies were watched over night and day to ensure that the Cat Sìth would not gain access to the corpse. Kitty distractions such as catnip and music were sometimes employed, as were games of leaping, wrestling, and riddles, all of which were thought to offer additional protection to unburied bodies.

|

| The Cat Sìth or Cat Sidhe photo: pinterest |

While some believed the Cat Sìth was a type of feline fairy, a common Celtic legend proclaimed that Cat Sìths were in fact witches who were capable of morphing into a magical cat eight times. Those attempting the transformation a ninth time would be permanently trapped in kitty form, hence initiating the myth that cats have nine lives.

The Yara-ma-yha-who

A cross between a vampire and the bogeyman in Australian Aboriginal folklore, the Yara-ma-yha-who is a strange, red-skinned humanoid that dwells in the branches of fig trees, waiting to drop on unsuspecting victims.

|

| Yara-ma-yha-who A Book of Creatures |

|

| Yara-ma-yha-who photo: villains.wikia.com |

The creature was said to have suckers attached to its hands and feet that it would use to drain its prey of blood, much like a giant leech. Once its victim was sufficiently weak, the Yara-ma-yha-who would ingest them whole, resting for awhile before regurgitating the person (still alive) and beginning the whole process again. With each regurgitation, the victim would return slightly shorter and a little bit redder in tone, finally becoming another Yara-ma-yha-who.

The Ijiraq

|

| Things That Go Bump — Ijiraq - A shapeshifter from Inuit mythology Tumblr |

An elusive Arctic shapeshifter found in Inuit mythology, the Ijiraq is said to live between the world of the living and that of the dead. The Ijiraq could take many forms, including that of a half-man, half-caribou monster called Tariaksuq, generally only seen when looked at from the corner of one’s eye. The shadowy form would vanish when looked upon directly.

|

| The Ijiraq photo: Pinterest |

In Inuit lore, the Ijiraq was a kidnapper of children, accused of stealing little ones to hide and then abandon in the Arctic cold. When a hunter stepped into the cursed Ijiraq’s territory he would become hopelessly lost and unable to find his way home.

|

| Librum Prodigiosum — The ijiraq is a shapeshifting creature |

Oddly enough, certain areas traditionally associated with Ijiraq activity are also home to large deposits of toxic sour gas, sulphur smoke, and geothermal activity. It’s possible that rising vapors sometimes created mirages; pockets of gas may even have been responsible for disorientation and hallucinations.

The Liderc

There are several types of Liderc in Hungarian folklore, all of which are said to hatch from the first egg of a black hen that has been kept warm in a human’s armpit or a heap of manure.

The egg eventually hatches to reveal a magic chicken, a small imp-like creature, or a full-grown woman or man, sometimes even taking the form of a deceased lover or family member. In addition to behaving as an incubus or sucubus and performing its owner’s every wish, the Liderc immensely enjoys hoarding riches.

|

| The Liderc photo: Pinterest |

Over time, the owner of a Liderc will accumulate great wealth, but the arrangement is a deal with the devil. Periodically, the Liderc crawls atop its owner’s chest, drinking his or her blood, and gradually leaves them more and more weak. The Hungarian word for nightmare is lidercnyomas, which literally means “Liderc pressure” from the feeling of having the creature’s weight upon one’s chest. The only way to be completely rid of a Liderc is to command it to perform an impossible task. After trying its hardest to comply, the Liderc will grow so consumed with frustration that it will essentially implode.

The Impundulu

Found in the folklore of several South African tribes, the Impundulu, or “Lightning bird,” is a human-sized vampiric bird said to cause lightning by setting its own fat on fire. It is heavily associated with tribal witchcraft, and is believed to be immortal, allowing it to be passed down as a familiar through generations of female witches.

|

| The hammerkop, one believed manifestation of the lightning bird photo: wikipedia |

The Impundulu was believed capable of morphing into human form to make love to his witch owner and to feed on the blood of her enemies, causing bad luck, sickness, and death.

|

| Impundulu the Lightning Bird – Southern Africa Travel |

Traditionally, when a man became ill it was not uncommon for his wife to be accused of secretly harboring an Impundulu.

Puckwudgies

The forest fairy of North America, Puckwudgies are found in the folklore of several American Indian tribes. Oddly similar to their Celtic counterparts, Puckwudgies are small, magical woodland beings with poison arrows and the ability to appear and disappear at will. Legend has it that the Puckwudgies were once a friend of humans, but an accumulation of grievances and jealousies caused the little guys to turn against us. They’ve been known to attack people, kidnap children, burn down homes, and lead travelers astray, and are sometimes even blamed for staging suicides by pushing their victims off cliffs.

|

| The Pukwudgies photo: Pinterest |

|

| Paranormal Encounters What Exactly Is A Puckwudgie? |

Certain forested parks and pockets of wilderness in New England are still said to be rampant with Puckwudgies.

Other articles on the same theme:

Story source:

The above post is reprinted from materials provided by Atlasobscura . Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.